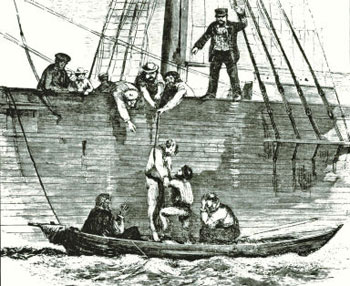

Imagine sitting enjoying a drink, you’re a healthy young man who just wants a beer. Suddenly, you hear a little click, and the ground drops out from under you. Or someone, knocks you in the head and you’re dragged to a cell where you wait with other young men. You’ve heard the tales; you know that within 24 hours you’ll be sold to a ship sailing for the Orient.

You’ve just been shanghaied.

Shanghaiing refers to the illegal capture and sale of able-bodied men to sea captains in need of a crewmen. In a law sense any sailor who had not soberly signed a ship's articles was considered to be shanghaied.

European law from the Middle Ages up to the 1800s allowed for men to be virtually enslaved to businesses and the military. Financial slavery was the most common form: by not paying sailors until the voyage’s end, and forcing them to “borrow” money to buy necessities, captains kept their crews in debt and thus in servitude.

“Impressment” was the military version of Shanghaiing . “Press gangs” of thugs intimidated men on the street into joining the military. The British navy’s impressment of American sailors was a major justification for the War of 1812. As impressments waned, shanghaiing began, with its glory days running from about 1850 to 1920.

Kidnappers known as “crimps” could earn $30 or more per head for providing men (sailors or not) for merchant ship crews. The practice was called shanghai because many West Coast ships indeed where headed for Shanghai, China in the booming days of the Asian trade; plus, Shanghaied sounded much less harsh then kidnapped.

Crimps of both sexes and all ethnicities ran saloons, casinos, boarding houses and similar businesses that provided lots of victims. Typically, shanghaiing involved drugging (usually with opium-laced liquor) and/or club the victim before dragging him onto a ship, where he would wake up too late.

Portland, Oregon and San Francisco were the shanghai capitals of the US. Portland has a network of tunnels form the period that were used, in part, to transport shanghaied victims to ships from trapdoors in saloon floors. (There’s now a tunnel tour that exaggerates the lurid aspects.)

Portland crimp Jim Turk reportedly shanghaied his own son, while Joseph “Bunco” Kelly infamously shanghaied 24 men he found dying after they drank formaldehyde; most were already dead when he shipped them. The Portland chief of police in 1890 was fired for engaging in crimping himself. And the top Portland crimper, a hard-punching scoundrel named Larry Sullivan, once boasted, “I am the law in Portland.”

San Francisco boasted James “Shanghai” Kelly, the “King of the Crimps,” who reportedly staged an open party with free (opium-laced) booze, thus shanghaiing 100 sailors. Super-crimp James Laflin, who bought victims from other crimps, actually kept an account book. It shows that in only four years of his 50-year career, he bought and sold more than 6,000 men.

Despite the scale and infamy of this hideous business, corrupt politicians looked the other way. (Some crimps even became California state legislators.) Meanwhile, naïve and desperate men continued to flood the waterfronts. Like today’s high-level drug traffickers, crimps defied law enforcement, bribing city officials and threatening captains, who accepted the system partly from fear. When Capt. James C. Cleary of the British vessel Blackwell resisted in the 1860s, his ship was burned to the water. Ships’ captains, however, cannot escape shouldering a share of the blame. Men like the infamous Robert H. (“Bully”) Waterman, who never denied being the most despotic of all American sailing masters, clubbed and flogged men, sometimes to death, for misreading a compass, responding too slowly to an order, or simply getting sick. Shanghaied landlubbers, knowing nothing of halyards, jackstays, and jib booms, suffered most of all. With no recourse and very little money, escape was difficult even when the ship was in port. Many a sailor knew that he could be arrested as a deserter even if his service had been involuntary. Because he was considered riffraff, few people cared. A fugitive-sailor law remained in effect for more than three decades after the fugitive-slave laws had been repealed.

Shanghaied men usually served at least a year aboard ship. They might then be paid. Or they might be handed back to a crimp for a cut of the profit.

Shanghaied men usually served at least a year aboard ship. They might then be paid. Or they might be handed back to a crimp for a cut of the profit.

Shanghaiing indeed generated desertions and mutinies galore, though many of them were stopped by violence. The law generally favored the captain, not the crew.

Unions and federal legislation attacked shanghaiing, notably the Maguire Act of 1895 and the White Act of 1898, before finally being eradicated by the Seamen's Act of 1915. But most historians of the subject agree it was killed mostly by the rise of the steamship, which required a specially trained crew. Steamships required less crew and those on board needed to be highly skilled to operate the complex engine were taking over the seas. The call for a drunken unskilled labor, being delivered in a canvas tarp waned. By the 1920s, the crimpers were out of business.

Sources;